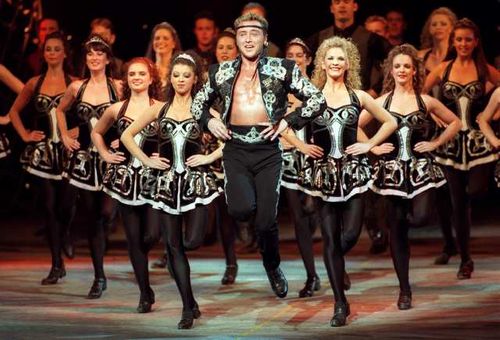

Riverdance at 20 and the Gael Force That First Struck Lightening Around the World

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

As the Globe and Mail’s fulltime dance critic, I witnessed first-hand the global phenomenon that was Riverdance. I also spent time in a Detroit-area hotel room (more on that later) with its original star, Michael Flately, a dancer with an ego as big as his Guiness World Record for more clicks per second than ever before achieved by a pair of jigging feet. After Riverdance the American hoofer went on to form Lord of the Dance, and, yes, lording it over legions who had overnight gone gaga for ethnic folk dance performed in sport stadiums. The memory lives on. A 20th anniversary Riverdance revival arrives in Toronto on May 17 for a limited run at Mirvish Theatre. In anticipation, we went back into the archives to revisit the fury that first made step dance sexy.

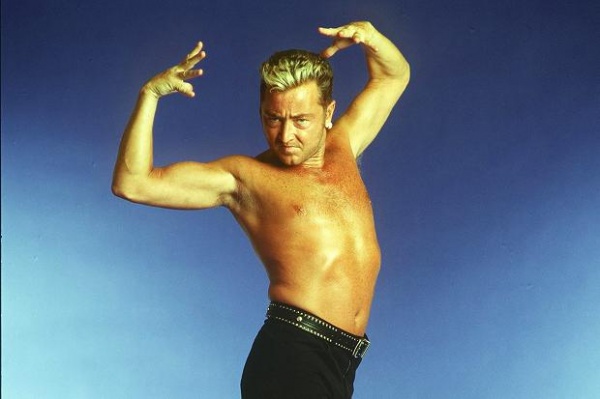

A bare-chested sex god with a penchant for tight pants, diamond earrings and cologne liberally applied, Michael Flatley is Lord of the Dance, the highest paid dancer in the world.

When the 38-year-old, Chicago-born star of the internationally acclaimed Irish dance show slinks onstage, wearing a headband and a bottle tan, the air-thumping crowd shrieks and throws roses.

“Do you want more?” he screams. He asks the question again and again until the deafening roar of more than 10,000 yeeeeahs finally satisfies.

With a sexy pout of the lips, Flatley peels off his sparkling matador jacket, emblazoned (in sequins) with the green, white and orange of the Irish flag, and dances a blazing riff across the floor.

The house rocks when two smoke bombs explode at the finale. This time the audience really goes berserk.

Glassy-eyed fans wearing long, hooded robes that make them look like Druids on drugs rush the stage and chant his name. Mi-chael. Mi-chael. Flatley flashes a charismatic smile. Knowing that people love him gives him the ultimate high.

“It’s energy,” he says, gasping for air backstage. “You’re out there pumping out that great energy, night after night after night. And the audience gives it all back. Do you know what that feeling is like? It’s bliss.”

Since its dazzling debut in Dublin last summer, Flatley’s unique brand of arena dance has consistently sold out stadiums normally reserved for sporting events and rock concerts. Featuring a stage design by Jonathan and Cheryl Park, the people who dressed up the Rolling Stones’ Voodoo Lounge tour, and a throbbing lighting show by Patrick Woodroffe, the person who lights Elton John, Michael Jackson and Tina Turner, Lord of the Dance has grossed in excess of $28-million on its current 20-city North American tour and another $140-million on CD and video sales.

The Gael force blows into Montreal’s Molson Centre Theatre tomorrow and Saturday, and Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens on Sunday and Monday. It descends on Vancouver in June. The shows have long been sold out.

Indeed, in Toronto, Flatley’s rejigged jig sold 18,000 tickets in less than 48 hours. The box office opened on March 22, a full two days before the Lord himself flashed his act in front of an international audience of nearly a billion people at the Oscars.

Critics tend to loathe him. His show is usually panned by reviewers who object to his unbridled stage bravado. One British review was headlined The Ego Has Landed.

“I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again,” Flatley says. “People mistake ego for self-confidence. I would say that you need to have an enormous amount of self-confidence to face 10,000 people on your own every night. That’s not an easy thing to do. And if you’re not confident at your job, you could never do that. You could just never do that. The more confidence you have, the more willing you are to walk on the edge and be out there in front of them.”

Though an innovator, Flatley was unceremoniously dropped from Riverdance — another touring Gaelic dance show that he helped create and once starred in — in 1995 when he had a very public falling-out with producer Moya Doherty over creative control. Flatley is now suing Riverdance for 2 per cent of the show’s profits (about $7-million). The matter has yet to go to trial. But Flatley is already airing his side of the story.

“They wanted 100-per-cent creative control over my work,” he says, his voice registering hurt. “You know, they wanted control and they weren’t even dancers. And considering I had brought over the dance style and taught it to the Irish people, I thought it was terribly unfair. I’m from America, and everything here is freedom of expression. But they tried to make me a caged animal and I couldn’t live with that.”

Despite Flatley’s critics, other dancers don’t begrudge him his success. “The only thing I can say about Michael Flatley is I think it’s wonderful if anyone can bring dance to the masses,” says National Ballet of Canada principal dancer Rex Harrington. “And he’s very smart because he’s making a lot of money doing it and I wish I had his pay cheque. I think it’s a good thing and I think that he’s obviously quite talented.”

Flatley’s Lord of the Dance is not just another in a series of Celtic revival shows spreading their lucky charm around the globe. By taking a centuries-old dance form and turning it into an international pop sensation, Flatley has created what some are calling the show of the decade.

Flately has what every performer wants — great word of mouth.

Though Riverdance and Lord of the Dance are different — the firstis a folkloric dance variety show while the secondis a Viva Las Vegas-styleextravaganza in which dance serves to tell a tale of good and evil in mythic Ireland — each has contributed to a radical redefining of Irish dancing as a popular art.

(Riverdance, which jumpstarted Flatley’s mammoth popularity, comes to Toronto next month, with a week of performances at the Hummingbird Centre. It too is already sold out.)

Irish dancing is traditionally a poker-back affair, with the arms held stiffly at the sides and the gaze decidedly mournful, as if thought was perpetually cast on the misery of British rule. The footwork, however, has always been lightning fast and the jumps buoyant, as if the fairies themselves were dancing a reel.

Flatley has freed the arms in Irish dancing and added a dollop of flash to the overall performing style. He also accentuates rhythm in the footwork, using counterpoint to bring out different tones in the tap to complement the music. His dances looks like a marriage of flamenco and step dancing, part sex and part romance.

“The truth is, you can’t really define what we do,” he says with a touch of the brogue. “The best definition I’ve ever heard anyone use to describe it is pop dance.”

A concert-level flutist whose feet (insured by Lloyd’s of London for more than $70-million) can tap out 28 clicks a second, Flatley often describes himself in animal terms. “I was kind of like a wild horse,” he says, recalling his boyhood lessons in a Chicago-area Irish dance school. “I wanted to do kicks over my head and I wanted to do everything. But I didn’t want to wear a kilt. It’s not that I was being disrespectful. I just never understood that.”

Flatley’s first dancing teacher, Marge Dennehy, “knew from his first lesson that he was going to be great,” she says from her Oak Lawn, Ill., home. He was 11 when he started, she recalls. “He went from beginners to competition level almost overnight. He skipped all the categories, which is very unusual.”

Flatley went on to become the first American to win the All World Championships in Irish dancing. For a while he was the world’s only professional Irish dancer, touring occasionally with the Chieftains. But the number of gigs that call for a jig were few and far between. For many years, Flatley sustained himself by working on construction.

For a while he laboured under his father, who until recent triple-bypass surgery was a tradesman with his own business who taught his five children (Flatley has three sisters and a younger brother) the value of hard work.

Flatley’s meteoric rise has ushered many changes into his life. His 11-year marriage to Polish make-up artist named Beata Dziaba broke up last year as a result of a ruthless touring schedule. He no longer has a home — “I live in hotels,” he sighs — and his body hates him for it.

Before and after every show he gets a special rub-down (female hands only) to loosen any knots in his muscles. Every night he soaks his feet in ice to make sure he can walk the next day. He says he can lose eight to 10 pounds dancing each show. And at a lean 5’9″, weighing in at 147 pounds, Flately doesn’t have fat to spare. But the pain is worth it. Lord of the Dance has made him a very rich man. In conversation he admits to making a weekly salary that is in excess of $630,000. When he was with Riverdance he made $105,000 a week.

Flatley says he gets his confidence from self-help books. He says he doesn’t watch television, doesn’t listen to the radio and doesn’t read fiction. Everything for him is focus, focus, focus. “Those are things for passing time,” he says.

Next on his agenda is a movie. It will be a dance film, he says, with a love story. He will star (of course). Production will begin next March.

“I think it’s really important in life, whatever you do, to do it your own way,” says Flatley. “I can’t tell you how many times in the tough years I would try to get work as a dancer and everyone wanted me to dance like a tap dancer. But I persevered. I didn’t want to do it that way. I’m not a tap dancer. I’m a Celt. And I do it a different way.”